It’s 7:15 AM on an overcast Thursday in May 2024. The Thames foreshore is deserted along the Southbank in Central London as the tide is going out. Being a mudlark with a permit from the Port of London Authority, I’m searching for historical artefacts lost, discarded or deposited in the river over thousands of years. Today I’m in my default state – crawling along the ground on my hands and knees in deep focus. Near the river wall I spot the tiniest sliver of pottery sticking out of the sand-covered mud. From the thickness and the salt-glazed surface I know it’s a piece of Rhenish stoneware. Tugging on it produces no movement so I know there’s more of it firmly embedded in there. As I free a beautiful big decorated fragment from the mud, the thought what if it’s a complete Bartmann jug? flashes through my mind. Bartmann (‘bearded man’ in German), or ‘Bellarmine’, jugs are a distinctive and durable type of 16th–18th century vessel made in Germany with a bulbous body and bearded facemask on the neck that were used for holding beer, wine or occasionally other substances such as mercury. A complete one is a holy grail bucket list find for a mudlark – have I just found mine? To my amazement the pieces just keep coming. I feverishly but carefully extract sherd after sherd, plain and decorated sections alike, until I turn over a huge beardy and grotesque face that stares back at me as if angry that I’ve woken him up from his centuries-long slumber in the mud. Finding a face on the foreshore is always a thrill. It’s now that I know for sure what I have – the majority of a clearly very large Bartmann jug dating to the 17th century, judging by the style of the facemask.

That morning over the space of one hour I found 108 jug fragments in a small area, just under the surface of the mud. This is lucky because I’m only allowed to dig up to 7.5cm on my standard foreshore permit. After filling my hole, the pieces went into a plastic carrier bag and I headed home, weighed down physically by what I’d found but bubbling with excitement at the inevitable research and reconstruction that awaited me.

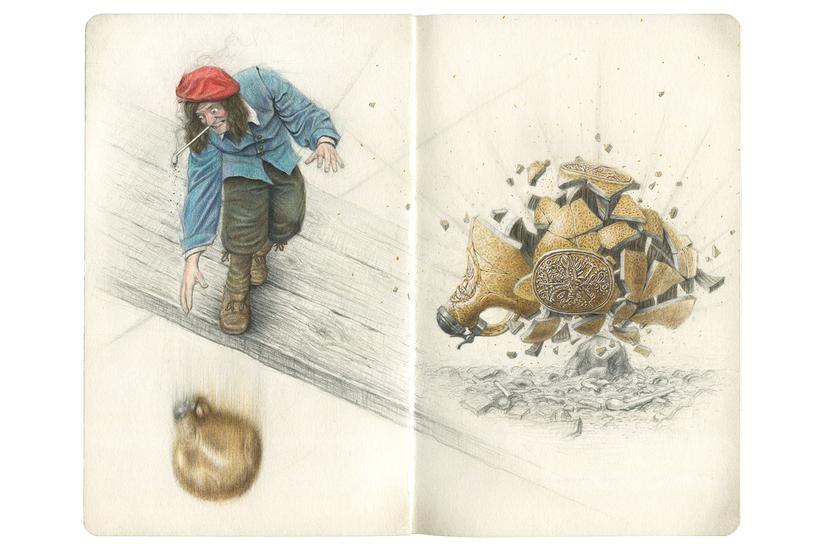

After cleaning every fragment, I began piecing them back together like a 3D jigsaw puzzle with the help of my partner, Alice. The jug gradually took shape over a month using HMG Paraloid B72, a reversible acrylic glue used by museums and conservators. After glueing, we positioned them in tubs of uncooked rice to keep them still whilst drying. This exciting, addictive and sometimes frustrating process culminated in a truly special end product – around 70% of a very large Bartmann jug with a complete facemask, three huge medallions, handle and a whole base that allows it to stand on its own. It’s so big that an average-sized Bartmann could fit inside!

People often say “wouldn’t it be great to find the rest”, but I love it as it is. I have all the best bits and the missing pieces will mostly be nondescript. I’ve searched the find spot many times since, including with Steve Camp, a member of the exclusive Society of Thames Mudlarks. He kindly used his membership privileges to dig deeper, but only two more fragments have turned up, taking the grand total to 110. Pieces may have since ended up in fellow mudlarks’ collections (and I’ve had others searching on my behalf!), but I feel so privileged to have stumbled across it on that first morning and rescued it before it was dispersed by the rough wakes of passing Thames Clipper boats. Its incompleteness also makes it more of an ‘artefact’ and allows one to peer inside and study the throwing lines left by the potter’s fingertips as they formed it on the wheel. As an artist, it also makes the perfect muse!

It’s always the star of the show on my table when I display my collection at mudlarking exhibitions, including the annual programme run by Hands on History as part of the Thames Festival Trust’s Totally Thames Festival. These events gather many mudlarks together to share their finds at historic venues such as St Paul’s Cathedral and London’s Roman Amphitheatre. They are always well attended by the public, who relish getting to see and hold objects and hear the stories behind what we’ve discovered. Bartmann fragments are no exception and you’ll find them on almost every table, demonstrating our collective fascination with this pottery.

Recently, visitors even got the opportunity to submit name suggestions for my jug, and out of 31 entries I can now reveal the winner to be ‘Bilbo’ the Bartmann (from now on I will refer to the jug by this name!). I know that Hobbits love their beer and I can definitely picture him in Bag End!

So what’s Bilbo’s story? I turned to books for my initial research. Bartmann jugs have chapters devoted to them in several brilliant books written by mudlarks, including MUDLARKS: Treasures from the Thames by Jason Sandy, Mudlark'd: Hidden Histories from the River Thames by Malcolm Russell and Sherd by Richard Hemery. There are also a number of go-to experts in all things Bartmann, but Alex Wright – founder and owner of the Bellarmine Museum (now shop) in Norfolk – was my first port of call. He is a highly experienced collector of Rhenish stoneware and is generous with his knowledge. Alex immediately told me it would’ve been a particularly grand jug and is not a common find. He pointed to an example that features in his book ‘The Bellarmine and Other German Stoneware II’ that has a very similar facemask and a single large medallion with a near-identical design to the three on mine. They were both probably made in Frechen, Germany – the main production centre – and it’s possible that their decoration was applied using moulds made by the same person.

Bilbo’s face is forever stuck in a grimace with an hourglass-shaped mouth. These faces started out smiley and well-sculpted in the early 16th century, but got progressively grumpier and more crude as time went on and production increased. His three medallions feature the double-headed eagle of the Holy Roman Empire, a political entity that dominated Central Europe from the Early Middle Ages to 1806. A small hole at the top of the handle tells us he would’ve once had a pewter lid. With all of this considered, he was likely made in the 1620s–30s.

But how did he end up in the Thames? A spider web of cracks on his back is evidence of an impact point. Did he smash into pieces when he hit the ground or did he enter the river whole and somehow break apart at a later date? Was he accidentally dropped off a ship while being unloaded onto the shore, destined for one of the many taverns or theatres in the ‘wild west’ that was 17th century Southwark? Was he already broken and thus discarded into the river, with his pewter lid having been melted down and repurposed? Or did he end up in the mud with rubble from a building destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666? We’ll never know for sure, but that opportunity to let your mind explore the possibilities is what makes mudlarking so intoxicating.

With my interest in this pottery well and truly piqued, the MOLA Academy of Specialist Training (MAAST) course on Bartmann jugs was the perfect opportunity to learn more. This free course was supported by ‘Bartmann Goes Global - the cultural impact of an iconic object in the early modern period’, a collaborative research project between MOLA (Museum of London Archaeology), LVR-LandesMuseum Bonn, LVR-Amt für Bodendenkmalpflege im Rheinland, and Tübingen University, with funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG).

Run by project members Jacqui Pearce and Nigel Jeffries, it was a chance to get up close and personal with many jugs from excavations across London. We delved into their history with regular lectures while cataloguing them for Bartmann Goes Global website (Submit a jug | MOLA), adding to our collective understanding of their reach and influence. You can find Bilbo here as well (1827872693 | MOLA). I also came away with a more accurate idea of what Bilbo’s story could've been. For instance, through Eliot Benbow’s talk on the trade in Rhenish stoneware (see his blog post), I learnt of Joos Croppenburg – probably the most prolific stoneware trader of the time – who imported at least a million pieces of stoneware from Dordrecht, The Netherlands between 1588–1625. Did Bilbo pass through his hands before eventually making his way to mine? It’s quite possible.

What I do know is that my discovery on that one lucky morning has opened up a whole world of intrigue and has made searching the Thames foreshore even more exciting, imagining the wonderful pieces of history that could still be out there waiting to be found!

Keep up with my finds and artwork @charlie.collects.