We find Rhenish stoneware and Bartmann jugs across Britain. They are in dozens of museum collections and regularly turn up during archaeological digs. But how did they get here?

Previous blogs have covered the journeys this stoneware took from the production sites at Frechen, Cologne and Raeren to the Netherlands. By the end of the 1500s, most Rhenish stoneware was imported into England via London, with a majority arriving from the Dutch port of Dordrecht (or Dort as it was usually called during this period).

A detail from the 1616 Visscher Panorama showing the London Riverfront. Millions of Bartmann jugs and stoneware vessels would have been unloaded from ships here in the 16th-17th centuries.

Stoneware imports to London: trading in the millions

The quantities being imported were vast. Between 10 to 15 million pieces of Rhenish stoneware passed through the Port of London between 1565 and 1640. These shipments can be tracked through the Port Books of Early Modern London. These are customs records, now kept at the National Archives. The Port Books record the imports and exports, which were tracked for taxation purposes. Fascinatingly, German stoneware can be seen in London customs documents from the earliest surviving records in the 1300s through to the end of the Port Books in the 1690s. This gives us a fantastic opportunity to track a very specific commodity over a long period of time.

“Alien” merchants and the trade in stoneware

Until at least the 1660s, almost all Rhenish stoneware imports into England were recorded in the Port Books as being by “aliens”. At this time “alien” was used to describe someone living in England who was born overseas. It comes from the Latin alienigena, which literally translates to ‘someone from a foreign country’.

Those described as “aliens” in this case were merchants from the Low Countries (Belgium and the Netherlands) and Germany, who were continuing a long tradition of importing everyday goods to England. Many of these merchants knew each other and often worked together. They also lived in the same parts of London – especially in the area of Somers Quay at Billingsgate, which had been associated with cargo traders from these countries since the 1400s.

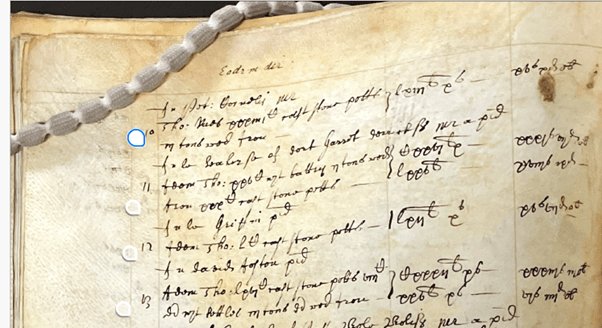

A detail from the London Port Book for 13th April 1632. One one day, a merchant called Thomas Rous [Rues] has imported four large cargoes of stoneware “stone potts” with other goods on ships from Dordrecht. Garret Derrickson, captain of one of the ships, the Seahorse, regularly transported stoneware between 1609-1632.

Stoneware merchants and their varied careers

Most stoneware merchants were not just selling ceramics, however. Joos Croppenburg (fl. 1578-1629), a major stoneware trader who is recorded in the Port Books importing at least a million pieces of stoneware from Dordrecht between 1588-1625, began his career selling humbler goods. These included heath (a material used for making brushes and brooms), frying and dripping pans, and large quantities of dress pins. In 1618 alone he imported over 13 million pins. However, by the early 1620s he had gained links with the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and was importing large quantities of spices including cloves, nutmeg, and mace. His stoneware trading was the most consistent aspect of his career and provided a stable income to branch out into other goods. He also traded large quantities of hops, an important ingredient for the beer brewing industry. This has a connection to his trade in Bartmann jugs, as they were often used for storing alcohol.

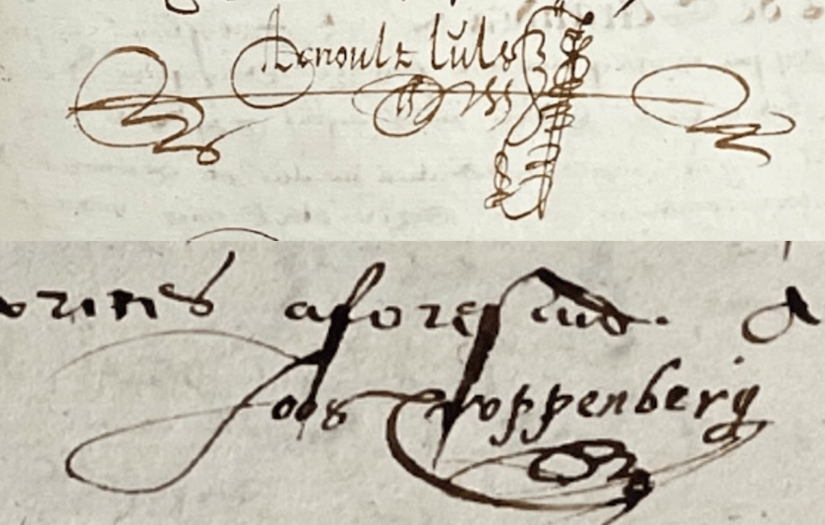

Another stoneware merchant with a varied career was Arnold Lulls (fl. 1584-1642). Originally from Antwerp, he is better known to historians as a prominent jeweller. A book of his jewellery designs even survives at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Nevertheless, Lulls also imported around 280,000 pieces of stoneware in 1609-1610. Many of the stoneware merchants also had shared business dealings. Lulls and Croppenburg, for instance, chartered voyages to the West Indies in 1609-10 to import large quantities of tobacco.

The signatures of Joos Croppenburg [Croppenberg] and Arnold Lulls [Arnoult Luls] in records of the High Court of Admiralty dating to 1598 and 1599.

Stoneware, London and England: the importance of the coastal trade

After being unloaded at several quays in the City of London, stoneware was traded through London and beyond via land routes. It was also carried by ship to coastal towns across England. Ports including Exeter, Colchester, Ipswich, Great Yarmouth, Boston, and Hull all received large amounts of stoneware from London in the 1500s-1600s. Stoneware was regularly shipped with glass, both drinking vessels and bottles.

This English coastal trade in stoneware may have developed in part because of the repeated attempts by the Dutch stoneware merchants to funnel the overseas trade solely through London. They tried to stop direct trade from Dordrecht to other English ports – probably to keep control over this important commodity.