Bartmann jugs were made in many different places across the Rhineland, but Frechen was at the heart of their production. From the mid-1500s this industry quickly gained momentum, and by the 1600s Frechen was mass-producing and selling Bartmann jugs for a wide range of domestic and international markets. This required a well-oiled system of trade, which this blog will focus on.

Most potters in Frechen were not involved in the trade with their products themselves. Instead, traders came from outside the town, mainly from Cologne or the Netherlands, bought the jugs, and organised their journey to the consumers. Often, they also made contracts with the potters beforehand, ordering a certain number of jugs to be produced and then took them off their hands. This system had the advantage that potters could just focus on their production and knowing their jugs would find a buyer. But it also led to the traders having an enormous amount of power. They could set the prices however high they liked, and the potters had to accept what was offered to them. Archival sources around Frechen record many court cases where potters were in huge amounts of debt to the traders. This led to seizing of their products and sometimes even eviction from their houses.

The typical trade route for Bartmann jugs from Frechen went along the river Rhine. Jugs were transported by land to Cologne, which is less than 10 km (about 6 miles) away. Some traders brought their wares to Cologne themselves and then contracted a shipper to deliver them to a certain destination. Other traders were shippers themselves, hiring someone to deliver their jugs to Cologne, and then accompanying them along the Rhine. However jugs’ journey was organised, they always remained the property of the trader who made the original contract with the potter. This applied to the entire journey, until they were sold at their final destination.

Anton Woensam: Image of Cologne 1531: smaller version of the originally 352 cm wide woodcut by Anton Woensam from Worms. Taken from: Henne am Rhyn, Dr. Otto: Kulturgeschichte des deutschen Volkes, Erster Band, Berlin, 1897, p. 387.

On their way along the Rhine, shippers had to pass many different customs posts. This means we can trace jugs in tariff and transit lists. In Germany, Bartmann jugs were usually transported empty and in great amounts. Sometimes shippers had more than one type of cargo, but mostly they just loaded their ships with the maximum number of jugs it could hold.

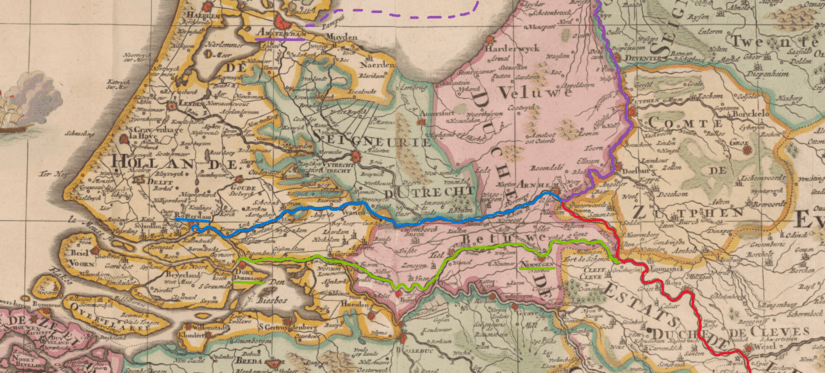

The traders’ destinations were usually somewhere in the Netherlands. Bartmann jugs could take three different routes, with some used more than others.

- The Nederrijn and Lek rivers were used to reach Rotterdam and ports for the North Sea.

- The Ijssel could be taken to reach Amsterdam.

- The Waal was used to reach Nijmegen and then Dordrecht.

This final route was the most important. It was also the route taken to reach England, which made up a significant amount of the whole Bartmann jug trade.

This map shows the rivers and their routes. The red line is the Rhine, the green is the Waal-Route, the blue is Neder-Rijn/Lek-Route, and the purple is the Ijssel-Route

Map taken from Nicolas Sanson: Provinces-Unies des Pays-Bas avec leurs acquisitions dans la Flandre, le Brabant, le Limbourg et le Lyege et les places qu’elles possedoient sur le Rhein, dans le duché de Cleves, et dans l’archevesché et eslectorat de Cologne / par le Sr. Sanson ; presenté à ... le Dauphin par ... Alexis Hubert Iaillot, ca. 1630, in: Jan Werner, De Atlas der Neederlanden: Kaarten van de Republiek en het prille Koninkrijk met 'Belgiën' en 'Coloniën'. Amsterdam 2013, nr. VI:8-9.